Avocados in Charts: How does the Mexican growers' strike compare to 2016?

In this ‘In Charts‘ series of mini-articles, Colin Fain of data visualization tool Agronometrics illustrates how the U.S. market is evolving. In each series, he will look at a different fruit commodity, focusing on a different origin or topic in each installment to see what factors are driving change.

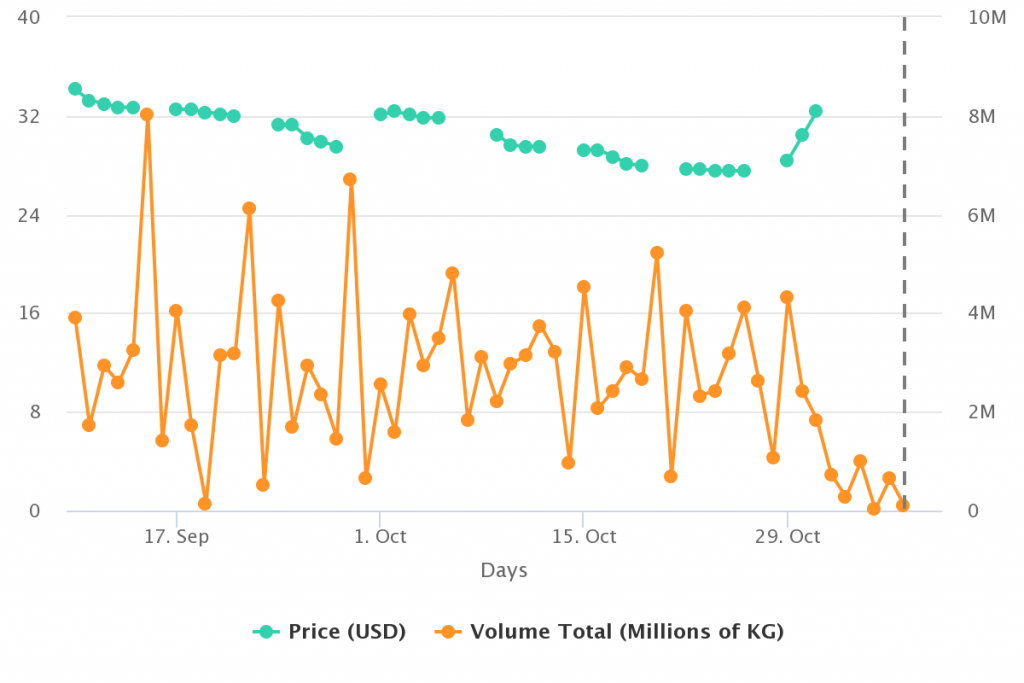

As Mexican producers head into the third week of strikes, volumes are falling away and prices are spiking. At least that’s what we could see while the USDA still had enough volume to report on prices which was only until October 31st.

This isn’t the first time Mexican producers have gone on strike, so I wanted to dive a bit into the data and see what insights we might gain from past strikes to help guide the stormy waters of that may lie ahead.

US Avocado Prices and Volumes

(Source: USDA Market News via Agronometrics)

The last time this happened was in 2016, when there were two events that caught my attention, and I think that both have lessons to offer.

The first event was a strike was right before the 4th of July promotion. The cause of the strike is relatively straightforward - with prices at a near-historic low, producers took matters into their own hands and stopped picking. This action cut the volume of exports and consequently, the price skyrocketed. The reason prices were so low to begin was because of an incredible 2015-16 season, which to date - with 870 million kilograms - is still the biggest on record, according to USDA data. It's also important to keep in mind that the strike happened in the middle of summer when demand is typically at its highest, so when volumes were cut back, the prices reacted strongly. The 2016-17 season, however, wasn’t quite as impressive, shipping 85% the volume of the previous season, and so prices remained pretty high from June onwards.

The second event happened in week 41, just three weeks earlier than when this current strike began. The massive drop in volume was due to organized gangs, external to the industry, which blockaded avocado shipments. The lower volumes managed to raise prices briefly before the markets re-aligned themselves. Of note is the period of time where this happened. In October and November, the U.S. gets cooler, leading to lower demand for avocados. This meant that the cut in volume didn’t have as big an effect on the markets as the first strike, and as soon as the volume got back to the market, the price came down quickly.

US Avocado Prices and Volumes in 2016

(Source: USDA Market News via Agronometrics)

So let’s set the stage. Comparing the volumes we are seeing today to 2016, an interesting comparison can be made between February, March and April which drove prices down that year, causing the strike. Of note are the returns this year, which were considerably higher, speaking to a healthy growth in demand and the market’s ability to absorb ever-growing volumes. I mention this period to use it as a base point with which to compare the two years.

US Historic Monthly Avocado Volumes

(Source: USDA Market News via Agronometrics)

September and October of this year, however, are quite different from 2016, where these months each saw the largest volumes to have ever arrived on the market. This volume will naturally bring down the price. However, we are still nowhere near the USD$20 per box growers were striking over in 2016.

US Historic Monthly Avocado Shipping Point Prices

(Source: USDA Market News via Agronometrics)

So what does this all boil down to? The avocado markets are as near a perfect commodity market as has ever existed. If you pull volume, for whatever reason, the prices will rise. Likewise, if you overproduce, prices will fall. These effects happen regardless of the reason for the lack of, or abundance of supply. The reason for that is because when a consumer goes to purchase an avocado, they are mostly driven by appetite and price. So if the price is too high, people will just buy less, if the price is lower, they can be compelled to purchase more.

These price changes are mostly driven by the need to move inventories, so if someone wants to simply set the price high, consumers won’t have an issue with it, but the inventories held by the retailers or shipper will never sell. On the other hand, if the price is set too low, shelves will be cleared of avocados frustrating customers and potentially killing future demand as they are forced to change their spending habits, shifting their purchases to other goods that are available.

If producers want higher prices in the long-term, there are only two ways of doing it - either increase demand… which is already happening (as can be seen by comparing prices and volumes during February, March, and April), or cut supply, either by planting less or finding alternative markets. Letting fruit simply go bad is also an option, but as long as there is a buck to be made it is worthwhile to pick the fruit that growers worked so hard to produce.

Another side effect of these shocks is also a loss in value of the fruit as waste is likely to increase when the industry rushes to get picked as quickly as they can to make up for the lost time. Also, the point of the year with the least demand is consistently Thanksgiving week. The closer we get to that date, the less demand there is for the fruit, offering fewer dollars for the same volume.

There is another scenario that could cause a strike that I am not able to write about objectively through the market data we work with - the distribution of profit throughout the supply chain. I personally believe that there should be a relationship between value added by a member of the supply chain and their profit, be it a retailer, distributor, receiver, shipper, producer, picker etc. The way the supply chains are set up now may or may not be as egalitarian as they should be.

I don’t pretend to know what the optimal profit distribution should be. My personal view is that all things being equal, each member of the supply chain should be able to argue for their own piece of the pie. The only way to be able to do so effectively, however, would be if there were complete transparency throughout the supply chain so that if any one actor is making unreasonable profits at the expense of the others they could be held to account. To the best of my knowledge, avocados are one of the most transparent fruits in the industry, with well-established systems for members to share information with each other.

That said, I know that it isn't 100% transparent and I understand why, for a slew of reasons, that is unlikely to happen. The reason I mention it is because should this have anything to do with the current strike, which I don’t know that it does, it would be worthwhile for all parties involved to find a better way to resolve their differences. Cutting off volumes doesn’t actually do anything to the markets as whatever volume gets there will be priced to move regardless, so the only thing the industry gets is added volatility and diminish the value of the fruit.

In our ‘In Charts’ series, we work to tell some of the stories that are moving the industry. Feel free to take a look at the other articles by clicking here.

Agronometrics is a data visualization tool built to help the industry make sense of the huge amounts of data that you depend on. We strive to help farmers, shippers, buyers, sellers, movers and shakers get an objective point of view on the markets to help them make informed strategic decisions. If you found the information and the charts from this article useful, feel free to visit us at www.agronometrics.com where you can easily recreate these same graphs, or explore the other 23 fruits we currently track, creating your own reports automatically updated with the latest data daily.

To welcome avocado professionals to the service we want to offer a 5% discount off your first month or year with the following coupon code: AVOCADOS

The code will only be good till the 20th of November 2018, so visit us today.