Irrigation scheduling and soil moisture sensors in cold hardy citrus

The content of this article 'Irrigation scheduling and soil moisture sensors in cold hardy citrus' was prepared by Charles Barrett of the University of Florida and has been revised and republished by FreshFruitPortal.com.

Soil moisture sensors are an incredibly valuable tool that can be used to make informed irrigation decisions and are even more valuable when combined with an irrigation schedule.

For Cold Hardy Citrus, there are critical times when water demand is increased, and a water deficit can reduce yield or fruit quality.

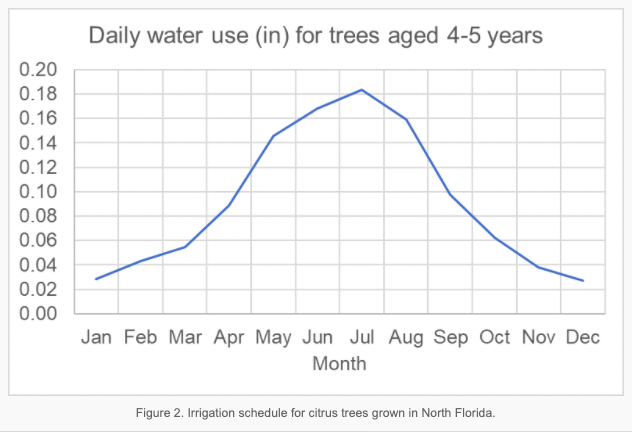

Charles Barrett has adapted some irrigation schedules for North Florida (figures 1-3) that were originally developed by Dr. Parsons and Dr. Morgan for Central and South Florida. There are several key concepts to keep in mind when irrigating any crop in Florida.

Key Points

- Frequent irrigation events are better than sporadic irrigation events. The irrigation amount should be shorter rather than longer. The point is, more frequent, small irrigation events keep water and nutrients in the root zone, mainly the upper 8-12 inches of the soil. When an irrigation event runs for too long, it can push water and nutrients past the root zone.

- Florida soils typically cannot store a lot of water, on average this amount is somewhere around 0.7-inch to 1.0 -inch per foot of soil. If the upper 12-inches of soil can hold 0.7-inch, it is not beneficial to apply more than 0.7-inch at any time. Most irrigation events should be between 0.25 and 0.5-inches.

- An acre inch, imagine one acre 43,560 ft2 covered with one inch of water, is 27,154 gallons of water. This number is useful in determining how many gallons are being applied and what that means as far as inches. If your emitters put out 15 gallons/hour (0.06 inches/min) on a 3-foot diameter circle (360° pattern), it’s the same as putting out 1-inch every 18 minutes. Therefore, irrigation events, after pressurizing, should be no more than 5-10 minutes assuming 100% application efficiency. Adding for things like evaporation loss and leakage, run times might creep up closer to 10-15 minutes after pressurizing the lines. These are short run times, but it is what the root zone can hold. Look at the schedules in figures 1-3, during certain times of year you can skip 3-4 days but at other times irrigation will be needed every other day. A great way to check if your run times are appropriate is by checking a soil moisture sensor see Figure 4-5.

Timing

Irrigation events made in the morning or late afternoon are less likely to be blown by the wind or evaporated by the sun, application efficiency is better during these times.

Can you or should you irrigate at night? Irrigating at night is fine, application efficiency is highest at night because the wind is typically calm, and evaporation is low.

Some argue that plants do not use water at night so you shouldn’t irrigate then but in practice, I’ve seen nighttime irrigation events are very helpful when trying to get a crop caught up after a pump was down for a few days and the crop was in drought stress. The thing to watch out for is to not irrigate too long, at any time, but especially at night.

I like to irrigate in the morning just prior to the crop demand really taking off, typically 6-8am. Then, if a second event is needed because the crop demand is high and you cannot get all the water needed by the crop out in a single event without pushing water past the root zone, I’ll irrigate again sometime during the last 2-3 hours of daylight.

The two events do not need to be equal time.

During high demand, more water is needed in the morning for the crop to use throughout the day.

The afternoon application is just enough water to refill the soil and help get the crop back to full turgor for the next morning. Turgor pressure is best understood as a physical indicator (appearance) of the crop, when the crop is wilted – turgor pressure is low, when the crop has good water content – turgor is high.

If a crop is wilted in the morning, when turgor pressure should be high, the crop is suffering from drought stress and is not getting enough water. Either there is water there and the root system is compromised (nematodes, etc.) or there has not been enough irrigation or rainfall to keep up with crop demand.

Please contact me if there are any questions or concerns, cebarrett@ufl.edu.

Check out the soil moisture sensor playlist on YouTube for more information on soil moisture sensors including where to place them in the field, how many are needed, and data interpretation.

Source: University of Florida