How smart-spray technology can reduce pesticide and fertilizer use for citrus growers

The content of this article 'How smart-spray technology can reduce pesticide and fertilizer use for citrus growers' was prepared by Brad Buck for the University of Florida and has been revised and republished by FreshFruitPortal.com.

Growers need to spray efficiently so they can apply pesticides and fertilizer only to crops – and minimize the chemicals that may contaminate natural resources.

As they battle the economically devastating citrus greening disease, farmers must look to control costs wherever possible.

With that in mind, Yiannis Ampatzidis is engaging artificial intelligence to develop a low-cost, smart tree-crop sprayer that can automatically detect citrus trees, calculate their height and leaf density and count fruit.

That way, the farmers target their spray more efficiently, so it lands on trees and leaves – and reduces chemical use by about 30%, compared to traditional spray methods.

Yiannis Ampatzidis, an agricultural engineer for UF/IFAS, uses artificial intelligence to develop a smart-tree sprayers.

“These smart technologies can save the fruit tree industry millions of dollars per year by optimizing chemical applications,” said Ampatzidis, a UF/IFAS associate professor of agricultural and biological engineering at the Southwest Florida Research and Education Center.

Smart-spray technology lets the grower vary the amount applied based on tree size and leaf density, and it will not spray if there is no tree or if a tree appears dead.

It also does not spray if it finds other objects, such as a water pump, a pole or a person, as examples.

“This new technology will further enhance the tree-profiling systems we have in place today, with the ability to detect and only spray the target foliage,” Ampatzidis said.

“Our data, collected by smart sensors, can control the amount of spray applied to the tree, in real time, and is stored in the controller to be downloaded for further processing.”

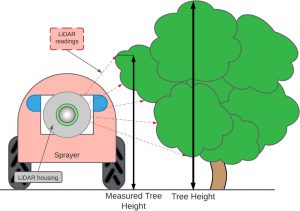

The system utilizes machine vision, GPS and LiDAR — a light detection and ranging remote sensing system.

Ampatzidis also developed algorithms to process the data as well as software to control the sensors.

The technology, cited in new research published by Ampatzidis, can also help farmers predict their crop yields.

To test the system, Ampatzidis conducted several experiments in citrus orchards at the center and in commercial farms and found they used less pesticide and fertilizer.

New technology applies more pesticide and fertilizers to fruit trees, meaning fewer chemicals in the environment.

Protecting citrus trees and their fruit makes up a significant chunk of any grower’s budget.

In Southwest Florida orange orchards alone, plant protection product applications cost about 34% of the total production costs.

An industry partner, Chemical Containers Inc, has evaluated the technology and entered an agreement with UF Innovate | Tech Licensing to license and commercialize the smart-spray technology.

As they continue to evaluate the system’s efficiency, Ampatzidis and his team will study how well it detects and sprays trees in fields with tall weeds in more commercial groves.

He and his team are also going to evaluate the system on other fruits, including peaches, apples and pecans to see how well it works on those tree crop systems.

“We also plan to develop smart fertilizer spreader applicators to improve nutrient management,” he said.

“Target-based management can help farmers apply nutrients as needed within the field, rather than applying fertilizers uniformly.”